Issue Position Paper

Teaching Librarians How To Teach

ACRL strives to advance equitable and inclusive pedagogical practices and environments for libraries to support student learning. To achieve this, the Association actively works to empower libraries to build sustainable, equitable, inclusive, and responsive information literacy programs, and to collaborate with internal and external partners to expand understanding of the impact of information literacy on student learning. - ACRL Mission for Information Literacy and Student Learning.

A central mission for the Association of College and Research Libraries, the preeminent national organization for college and university academic librarians is teaching information literacy. The section responsible for developing a national strategy on information literacy includes a focus on student learning. This issue paper will address the degree to which the goal of student learning for information literacy is addressed as a professional consideration for librarian education through a review of how academic librarians are prepared in MLIS programs. Specifically, this paper looks at the nature of the courses offered to MLIS students in a random selection of 20 programs from the 64 American Library Association (ALA) accredited MLIS programs in the U.S. and will propose the adoption of critical pedagogical frameworks for addressing shortfalls in the existing curriculum. This issue emerged as a first step in considering the topic of information literacy instruction for non-traditional students in library instruction. In order to fully understand the nature of the problem in addressing non-traditional students in academic settings it is important to understand how librarians arrive at academic institutions’ libraries (this issue paper) and then move into ideas for how they can best create targeted interventions to meet the needs of this community (future directions)

Problem Statement

The problem this paper addresses is a lack of pedagogical instruction for librarians throughout the MLIS curriculum in ALA accredited programs. The problem is twofold. In the first, there is generally a lack of pedagogical instruction for librarians in training in MLIS programs. Secondly, to the extent that such pedagogy instruction exists, the focus of the pedagogical instruction avoids engagement with critical pedagogy, which is of particular interest and value to serving non-traditional student populations. This problem is a contextual one, and has evolved and changed over time in response to changes in the relationship between the college/university and the library, as well as, in response to changes in digital technologies adopted in the library, and in response to social, political and economic changes more broadly.

Following the end of World War II, the need for a more highly skilled workforce precipitated a rapid shift in the role higher education played in American society. Stephen Atkins, writing about the history of the academic library in the U.S. recognizes that the post-war period saw significant growth every decade with all of the growing pains that such growth entails. The National Center for Education Statistics reports on trends in education across the U.S. They reported that in the post-war period the population of college students enrolling in institutions of higher education grew every decade until late 2000’s, and the10-year period between 2009 and 2019 was the first time there had been a decline in the number of students enrolling. Even after the decline in the last decade, there still is a historically high number of people enrolled today. NTS have followed the trends of higher education as well. Peaking in 2011, the transfer student population was 1.5 million (for comparison the total student enrollment for all undergraduate higher education in the same year was roughly 11 million) before it began to slightly decline. These trends mean that there are millions of students impacted by the decisions that libraries and librarians make in how they approach literacy instruction.

During the last 20 years there has also been a shift in the technologies used in the library and the ways in which libraries are engaging their communities. John Budd, writing about the evolution of contemporary academic libraries, and about collection development and access specifically, that, “higher education aims to foster learning through discovery” which has been greatly impacted by increase in the electronic and digital technologies introduced into the library. The shift away from traditional paper bound collection tools into digital catalogs and online databases means that the ways in which students engage with the library now require an additional layer of technical expertise that had been predominantly the providence of librarians themselves. As a result of this technical need, there is now an increasing need for a concomitant structure for teaching and learning information literacy.

Barbara Dewey studies the nature of the library and its relationship to the college or university as an institution using an organizational theory lens, and her insights offer another way of contextualizing the contemporary academic library. In her description of the academic library she articulates, “the library’s budget comprises a major and visible part of an institution’s budget.” The highly visible nature of the library budget also often makes it the focus of efforts towards neo-liberalization, with the emergence of institutional advancement bodies within the library focused on revenue generation, as well as an emerging trend towards the datafication of all aspects of the services offered by the library. In many ways the data process and the funding models are intricately intertwined, in some respects to good use but in many respects to less desirable ends. Atkins, describing the changing nature of the library, technology and budgeting states, “the problem for most librarians is dealing with a limited or no-growth budget.” In this context, the academic library is responding to a growing need for newer and more complex digital tools to do their work while maintaining physical collections, and doing so without the benefit of a similarly growing budget to meet the need. In short, the problem which this issue paper sets out to address is not the only programmatic change needed in libraries or MLIS programs, but rather is one of a host of elements which require increased attention and funding writ large.

Data Collection and Research Questions

The ALA accredits 63 MLIS programs in North America. In order to determine statistically relevant data at the 95% confidence level with a margin of error at 5%, 55 of the 63 programs would need to be coded. For the purpose of this issue paper, only a random portion of that group (20) was actually observed since the time and scale boundaries of this assessment did not necessarily require developing an independent cohort of coders, and since the intention is to be descriptive and exploratory, as a basis for future research and interventions. However, it would be ideal to come back to this population in the future and develop a more rigorous study in order to get more representative data.

H1: There will be a low prevalence of focus on pedagogy.

H2: Critical Pedagogy will not feature prominently in the limited pedagogical courses offered.

Findings

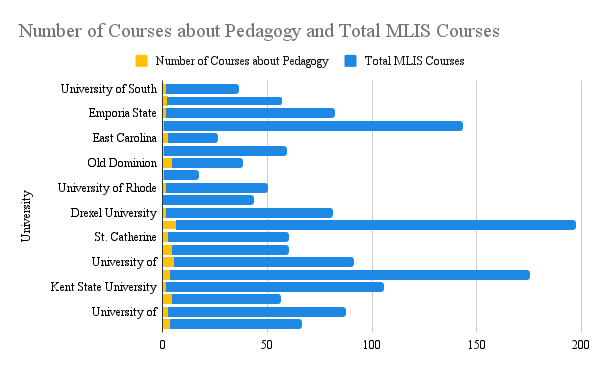

In the 20 programs under review there were 1,469 courses offered. Of those 1,469 only 60 (4%) of the course descriptions included key instructional training concepts like pedagogy, curriculum development, instructional design, etc. Table A shows the relationship between the number of courses offered in the LIS discipline and the number of courses offered that are pedagogical in nature.

Table A: Number of Courses Related to Pedagogy compared to Total MLIS Course Offerings

The University of Illinois, Urbana Champaign hosted the highest number of courses related to pedagogy (7), while data was not available for the University of Denver due to a technical issue being worked on during the data collection, three institutions only offered one course related to pedagogy in their program. As a portion of their total course offerings, Old Dominion’s program had the higher proportion of pedagogy related courses at 15.15%, while the University of British Columbia had the lowest at 0.7%.

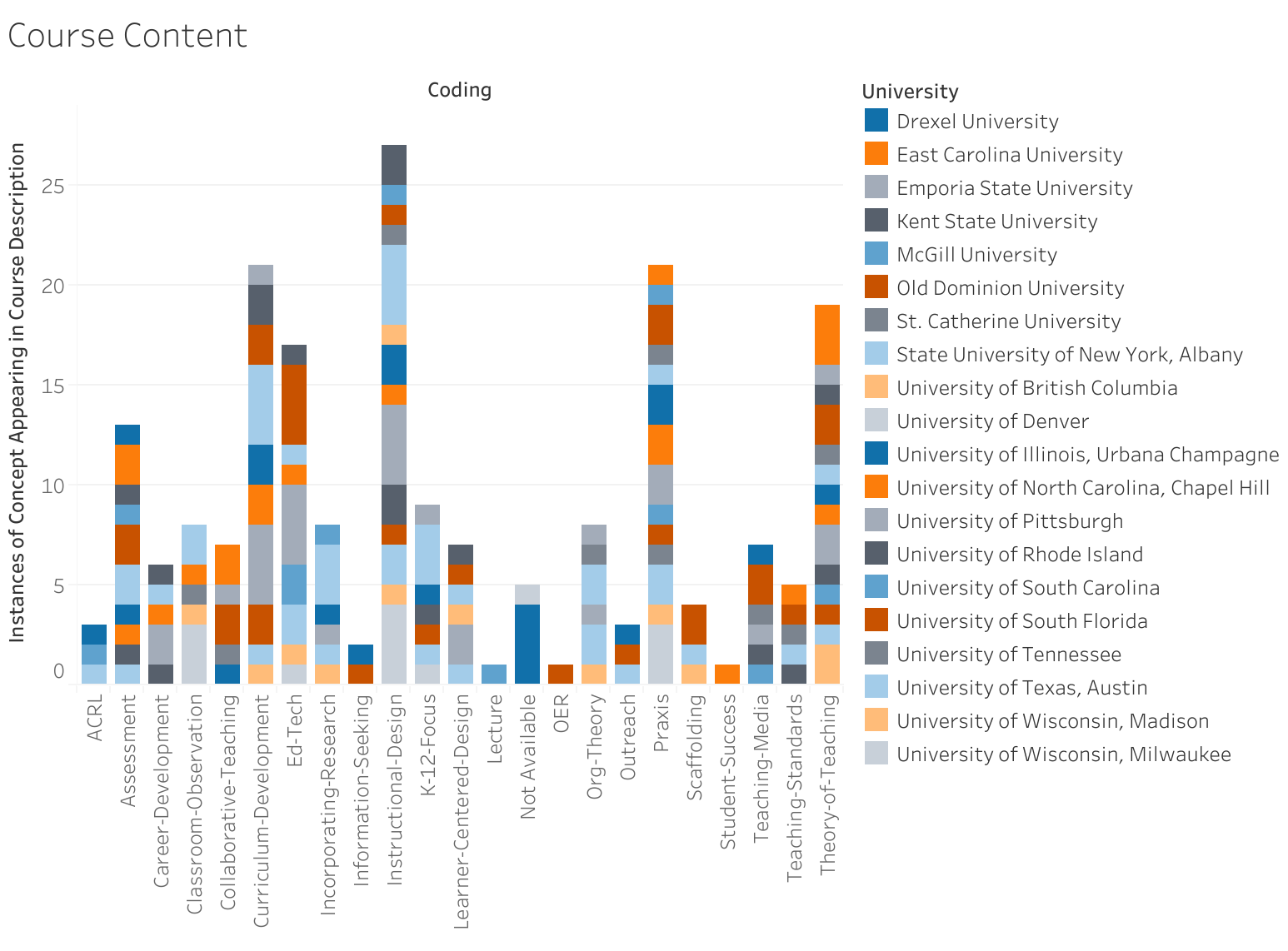

Several key themes emerged from the courses that were identified as being about pedagogy that were coded through a reading of the course descriptions. Table B shows the major themes that were identified.

Table B: Pedagogy Course Content Analysis

The most common themes were Instructional Design (ID), Curriculum Development (CD), Praxis, Theory-of-Teaching (ToT) and Ed-Tech (ET). The top three of these, ID, CD, and Praxis appeared in more than a third of the 60 courses offered on pedagogy, while the next two (ToT and ET) appeared in between 28-33% of the courses offered. Assessment, which fell in the 6th position of frequency for the coding frame, was also noticeably higher than the remaining classifications appearing in approximately 21% of the courses offered. The University of Pittsburgh was the only institution that offered a course that explicitly includes a critical pedagogy framing.

Based on the above data collected regarding the number of pedagogy courses being offered at the 20 institutions under review being less than 4%, Hypothesis 1 is accepted. Based on the existence of the single course on critical pedagogy (0.06% of total courses offered at the 20 universities), Hypothesis 2 is accepted.

While these assumptions are accepted based on the data collected, this data was not rigorous or representative and such the findings should be taken in that context. However, this does indicate that there may be value in continuing to study this phenomenon in the future using a more representative and more rigorous approach. Other key limitations to identify are the reliance on the course descriptions, which is not always representative of the actual content of a course, limitations of varying website configurations for courses in areas like ‘special topics’ as some institutions will offer numerous iterations of this course with different content but only some differentiate and identify them in the catalog. Lastly, there may be a coding bias as only the author is engaged in the coding of these courses and thus could present a single point failure in any coding of the content.

Proposed Solutions

This issue paper has identified key failing in the MLIS education programs under review which may indicate there is a broader need for MLIS programs to do a better job of preparing librarians to teach through instruction in pedagogy. Two solutions are proposed:

Proposal 1: Adoption of an increased number pedagogy related courses in the MLIS curriculum across all institutions.

Proposal 2: Engagement with departments of education in order to better be able to offer pedagogical approaches and techniques that stay current with the academic literature on theories of teaching and learning.

Future Direction

As there was such a limited number of cases where critical pedagogy even appeared in the institutions under review, it is hard to make broad determinations about its use and adoption in teaching in the library contexts. As such, this paper recommends further research into how prevalent critical pedagogy is in the LIS field and engaging in this concept as a theoretical framing in order to better build and understand how it may best be used in the field. This is likely best accomplished by both theoretical inquiry and interdisciplinary research within the field of education. Additionally, surveys of librarians and students who receive library instruction may be able to identify ways in which critical pedagogy appears but is not explicit.

Recommended Action

It is clear from the exploratory research that there is a need for more continuing research into this area. Additionally, institutions do not have to wait to begin to implement changes that would positively impact the teaching experience given to student librarians in MLIS programs. I would recommend the immediate development of a more rigorous course of study being made available to MLIS students across the board in relation to pedagogy. I would additionally recommend that institutions identify leaders in the use of critical pedagogy to engage programs in thoughtful leadership in the space, now is the opportune time to emerge as a model program in this regard so that other institutions can see the benefits of the adoption of such a model.

Moving Forward

As an incoming doctoral candidate, I intend to continue to engage this space as a field of research and as a librarian I see value in continuing to try to shape the future of MLIS programs so that future colleagues come into the academic library more prepared to teach, with more innovative and skills-based approaches that will best serve learners in the library.